Buddhist Art

Shakyamuni Stong Sku (or 1000 Bodies) / 20th century, Tibetan Thangka, 2002.4.9, Gift of Bruce Walker '53

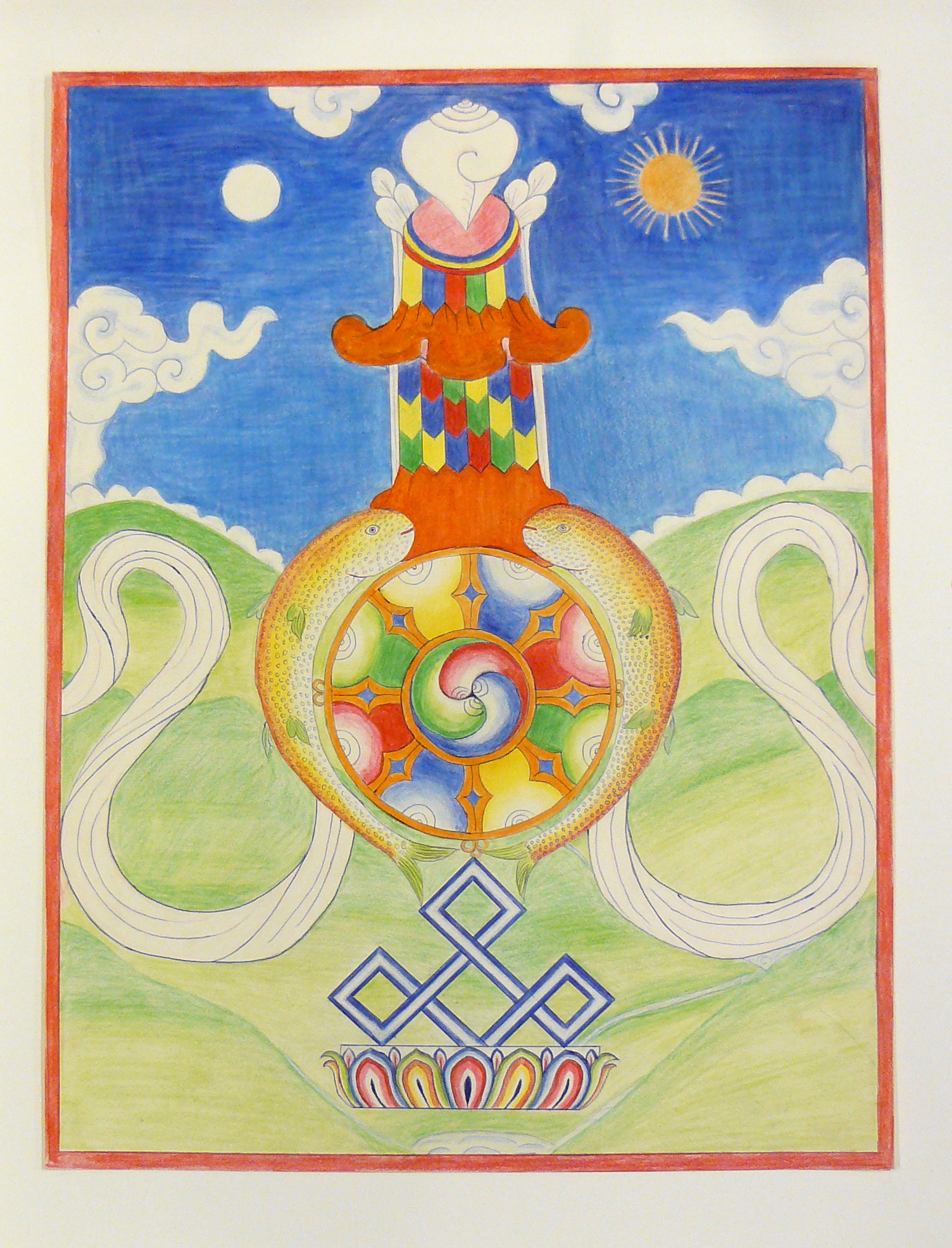

Drawing of Eight Sacred Emblems of Buddhism Tibetan, 1960 - 1964 colored pencil on paper Gift of Bruce Walker '53, 2004.2.7

Butsudan (private Buddhist altarpiece) Japanese, c. 16th century carved and gilded wood Gift of OGATA Sennosuke, 1885.1.1

A Brief History

Buddhism was founded by Siddhartha Gautama, also known as the Buddha or “Enlightened One”, who lived from 566 to 480 B.C. Gautama was born into the family of a wealthy warrior-king and lived an extravagant life. As he bored of royal life, he decided to wander the world in search of understanding and renounced his title to become a monk. One day while meditating beneath a tree, Gautama finally understood how to be free from suffering and achieve salvation. He then dedicated his life to spread his understandings throughout India.

Four Noble Truths

The Four Noble Truths are the core of the Buddha’s teachings. The First Noble Truth is the truth of suffering, or the truth that suffering exists. The Second Noble Truth is the truth of the cause of suffering. In Buddhism, desire and ignorance lie at the root of suffering. Vices, such as greed, envy, hatred, and anger derive from both desire and ignorance. The Third Noble Truth states that there is an end to suffering through achieving Nirvana, a transcendent state free from suffering and the worldly cycle of birth and rebirth. The fourth and final truth lays down the path to attaining the end of suffering, known as the Noble Eightfold Path. The steps of the Eightfold Path are Right Understanding, Right Thought, Right Speech, Right Action, Right Livelihood, Right Effort, Right Mindfulness, and Right Concentration.

Karma

In Buddhism, Karma refers to the good or bad actions a person takes during their lifetime. Good actions bring about happiness in the long run and bad actions bring about unhappiness in the long run. There is also neutral karma, which derives from acts such as breathing, eating, and sleeping, and has no benefits or costs. The karma weight that certain actions carry is determined by their frequency, intentionality, and if they are performed without regret, against extraordinary persons, or towards someone who has helped in the past. Karma is a main factor in the Buddhist cycle of rebirth, as it determines the realm into which living things can be reborn.

The Cycle of Rebirth

There are six planes into which living beings can be reborn. Those with positive karma are reborn into one of the three fortunate realms: the realms of demigods, gods, and men. Those with negative karma are reborn into the realms of animals, ghosts, and hell. The realm of man is considered the highest realm of rebirth because they are free from relentless conflict and suffer less suffering than all other realms. Also, men have the opportunity to achieve Nirvana, something that the other realms lack.

Buddha Imagery Interactive

Images of Buddha can be found throughout this art collection, and may look very similar. The most common type of image shows the Buddha in a lotus position during meditation, which represents both the importance of meditation in his life and the moment of his Enlightenment. His eyes are closed, the soles of his feet visible, and his hands rest in his lap (the Dyhana Mudra). To find out more about the different ways Buddha is depicted, click the link below.

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/ancient/deciphering-buddha-imagery.html

Sources:

http://www.pbs.org/edens/thailand/buddhism.htm

Sculptures and Altarpieces

Head of Buddha

Thailand, 19th century

bronze

Gift of Arthur E. Klauser '45, 1991.11.99

Head of Buddha

Thailand, 14th century

bronze

Gift of Arthur E. Klauser '45, 1991.11.98

Butsudan (private Buddhist altarpiece) with Benzai Ten

Japanese, 18th century

carved and gilded wood

Gift of Arthur E. Klauser '45, 1991.11.145

Butsudan (private Buddhist altarpiece)

Japanese, c. 16th century

carved and gilded wood

Gift of OGATA Sennosuke, 1885.1.1

Butsudan with Jizo Bosatsu

Japanese, 17th century

carved and gilded wood

Gift of Arthur E. Klauser '45, 1991.11.143

Mandala

The Diamond Mandala

Japanese, 15th Century

Watercolor on Cloth

Gift of Arthur E. lauser, 1991.11.262

The Diamond Mandala is one half of the Ryokai Mandara, or Mandalas of the Two Worlds. The Mandala is usually displayed in Japanese Shingon temples on the west wall. It depicts the Five Wisdom Buddhas of the Diamond Realm, which represents the unchanging cosmic principle of the Buddah. The Womb Mandala, also in DePauw’s collection, is currently in storage to prevent deterioration from light.

Prince Shotoku

Seated Figure of Prince Shotoku

Japanese, late 17th century

carved and gilded wood

Gift of Arthur E. Klauser '45, 1990.18.1

Shotoku Taishi (574 – 622 AD) was the Prince-Regent of the Asuka Period (538 – 710 AD) as well as the leading patron of Buddhism in the 6th and early 7th century in Japan. This figure of Prince Shotoku holding a ritual baton was found on the grounds of Wakakusa-dera, a temple in the Yamato province (now Nara prefecture) where he is said to have resided from 605AD.

For more information on Prince Shotoku, google “A Pictorial Biography of Prince Shotoku” and visit the digitized issue of The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin (January 1967).

Tibetan Thangkas

Padmasambhava Thangka

Tibetan, 19th century

ground mineral pigment on cotton and silk

Gift of Bruce Walker '53, 2002.4.2

Padmasambhava, also known as Guru rinpoche (Precious Teacher), was the adept Indian yogi from the present regions of northern Pakistan and Afghanistan who brought Buddhism to Tibet in the 8th Century. Regarded as the spiritual father of Tibetan Buddhism and founder of the Nyingma Sect, Padmasambhava is credited with "taming" and incorporating the many indigenous deities (Tsug), demons and spirits that are linked with animistic elements of Tibet's landscape into the Buddhist pantheon. Invited to Tibet by the 8th Century King, Tri Song Detsen, Padmasambhava in renowned for subduing negative energies and political obstacles that were preventing the construction of Samye, Tibet's first Buddhist monastery.

Shakyamuni Stong Sku (or 1000 Bodies) Thangka

Tibetan, early 20th century

ground mineral pigment on cotton and silk

Gift of Bruce Walker '53, 2002.4.9

Seated cross-legged in the center of this thangka is Shakyamuni, also known as Gautama Buddha, is the Buddha of our current historical period. As the young prince Siddhartha, shakyamuni sought and obtained enlightenment after renouncing his kingdom, discovering the "Middle Path" and teaching Buddhism for forty-five years. He is shown seated in the meditation position, and is surrounded by images of forty-nine Buddhas in the background. Three of the thirty-two physical signs of a Great Being (lakshanas) are visible in this depiction of Shakyamuni. Beginning at the top of the head, the ushnisha (crown-protrusion), symbolizes the cosmic openness of enlightened being's consciousness. Between his eyes is the urna, a small tuft of white hair that grows at the spot where a fierce deity has a third eye. Visible on the palm of his left hand and the sole of his left foot, are golden chakras. Marks such as the ushnisha and urna are found on almost every Buddha, however, the chakras are rarely depicted. Shakyamuni is shown here wearing patched monks robes, reminiscent of the earliest followers of Buddhism. His royal origins are marked by his elongated earlobes, which would have been stretched from wearing heavy jewels.

There are six combinations of seated postures (asanas) and hand positions (muduras) represented and repeated in this thangka. All figures of Shakyamuni rest in dhyanasana, the meditative pose, with the legs locked and both feet visible. The main figure holds his hands close to his heart in dharmackara, the teaching mudra. Depicting generosity, Shakyamuni is also shown with his right hand in the varada mudra (upside down with palm outward) and his left palm turned upward in his lap in the gesture of meditation (dhyana). Other depictions of shakyamuni include: both hands in meditation; left hand int he teaching mudra with the right hand in meditation; left hand teaching with the right hand in the gesture of fearlessness (flat with palm turned toward the ground); and right hand draped over the knee, middle finger touching the earth (bhumisparsa) while the left hand rests in meditation. The repeated images of Shakyamuni were completed in order for the artist and viewer to gain merit.

Drawing of Eight Sacred Emblems of Buddhism

Tibetan, 1960 - 1964

colored pencil on paper

Gift of Bruce Walker '53, 2004.2.7

Drawn by an amateur artist, the picture above is part of a rare collection of 10 Tibetan pencil drawings in the DePauw University permanent art collection. Created by young men in their 20s and 30s at Camp Hale in Leadville, Colorado, they were trained to work as radio operators and members of small guerrilla teams with the purpose of returning to Tibet for clandestine operations. Bruce Walker '53 was one of the CIA instructors at Camp Hale.

The Shitennō, Guardian Kings of the Four Directions

Known as the Four Heavenly Kings, these figures are positioned at the four corners of Japanese Buddhist altars, each watching over a different cardinal direction. As deities, they protect from evil spirits – psychological states that go against the Buddha and his message of freedom from suffering. The examples displayed here were likely intended for the altar of a smaller worship space, rather than that of a large temple. The Shitennō are usually portrayed dressed in armor, carrying symbolic weapons or objects, and standing on a demonic figure - signifying their dominance over enemies of Buddhism.

Not on display: Jikoku-ten, Guardian of the East

Bishamon-ten, Guardian King of the North

Known as Bishamon-ten in Japan, where he is the only Shitennō worshipped individually, Tamon-ten is the omniscient leader of the Shitennō and the most powerful of them. As the protector of Buddhism and its faithful, he is the patron of warriors, the punisher of evil-doers, and one of Japan’s Seven Lucky Gods – the bringer of wealth and prosperity. He is portrayed here holding a trident - symbolizing triumph over ignorance - and a miniature stupa (a structure that houses religious relics), representing Buddhist thought and the treasures of Buddha’s teachings, which Bishamon-ten both protects and dispenses to the worthy.

Bishamon-ten, Guardian King of the North

Japanese, 1420-1500 C.E.

carved wood with traces of pigment

Gift of Arthur E. Klauser '45, 1991.11.140a-b

Kômoku-ten, Guardian of the West

Literally meaning “wide-eyed” or “expansive vision,” Kōmokuten sees through evil (“suffering” in Buddhism), punishes it, and encourages enlightenment within others as well. He is often depicted with a scroll in one hand and writing brush in the other, but is portrayed here with a pilgrim’s staff adorned with fly-whisks, used to frighten or brush away insects, snakes, and tiny animals to ensure that the user does not accidentally kill any life form, following Buddhist law. With this staff, Kōmoku-ten shows others the way toward Enlightenment by example.

Kômoku-ten, Guardian King of the West

Japanese, c. 1000 C.E.

carved wood with traces of pigment

Gift of Arthur E. Klauser '45, 1991.11.136a-b

Zocho-ten, Guardian King of the South

Literally meaning, “lord who expands” or “lord who enlarges,” Zocho-ten’s additional role other than guardian is that of a catalyst for spiritual growth. Portrayed here in his most common pose, he wields a halberd, which he uses to cut away ignorance - one of the “three poisons” of Buddhism and a hindrance to spiritual growth.

Zocho-ten, Guardian of the South

Japanese, c. 1500 C.E.

carved wood with traces of pigment

Gift of Arthur E. Klauser '45, 1991.11.139a-b