Maps in Four Dimensions

August 10, 2009

Professor of Geosciences M. Scott Wilkerson's classes have changed a great deal from when he first started teaching 14 years ago. Gone are the days of poring over flat maps of locations such as Mount Vesuvius.  Without even leaving campus, he and his students are now able to stand at the center of Pompeii's ruins and look up at the giant volcano that buried the Roman city in 79 CE.

Without even leaving campus, he and his students are now able to stand at the center of Pompeii's ruins and look up at the giant volcano that buried the Roman city in 79 CE.

Wilkerson uses Google Earth™, which combines high-resolution satellite and aerial photography with three-dimensional terrain, to create "Geotours," virtual field trips in which students can interact with the geology in its spatial context.

"I can show a map on a slide and talk about it, but for a student to actually see it in 3D and manipulate his or her perspective, especially with the detail of the imagery, really brings the location alive," Wilkerson says. "Until you can fly around a volcano and see the scale of the geological forces we're talking about, you can't really understand them. It's not just a static map anymore; it's a dynamic object."

"When we talk about pyroclastic flow, students can actually see it simulated," Wilkerson says. To demonstrate, he opens up a Geotour of Mount Vesuvius. The perspective on the computer monitor moves into Vesuvius' crater before launching out, following the path of hot ash as it barrels toward Pompeii. It's the difference between reading about G-forces and riding a rollercoaster.

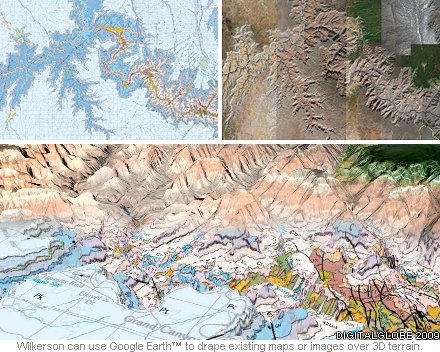

Bringing up an aerial view of Mount St. Helens, Wilkerson shows other maps, photographs or videos can be combined into a stand-alone package in the software. For example, an illustrated map of the devastated area following the 1980 eruption can be draped over the 3D model. Research photographs, attached to the points on the map where they were taken, show how this region has changed over the years. While any person can freely download the software and explore the same location, it's the addition of these other resources that make Wilkerson's Geotours useful in a college classroom. He and his wife, M. Beth Wilkerson, a geographic information systems (GIS) specialist at DePauw, recently collaborated on a Geotours workbook to accompany the third edition of Essentials of Geology, an introductory textbook that the Department of Geosciences use in their GEOS 110 classes.

The ability for researchers to incorporate their own project-specific information into the Google Earth™ software makes it an excellent supplement to field work. Having traveled to a location before – if only virtually – can save time, effort and money.

"When I was going through school as an undergraduate, we used a topographic map with contour lines to locate ourselves in the field. Now, with satellite images and 3D terrain, students in our geologic field experiences course can use the software to create a preliminary map of the features we're studying before we even arrive there. It allows us to get much more work done."

When Wilkerson visited the site of the Battle of Gettysburg, he stood on one of the ridges he'd explored in Google Earth™. "I had done a project for DePauw's GIS Day on the influence of geology on the battle. When I stood where the Confederate lines were and looked over towards the Union lines, it was impressive to see that the Union forces really were up higher because of the thicker igneous intrusion. I'd flown all over the location in the software, and it was very similar to what I had seen."

But Wilkerson is quick to point out that realism doesn't replace reality. "You'll never be able to replace actual field research," Wilkerson says. "Our geosciences department has a very strong field trip program, and we take students all over the world. However, what this software does is bring more geographic diversity to the classroom than ever before. We can't visit every single place in the world, but we can take classic locations – Mount St. Helens, the Grand Canyon or the Alps, for example – and incorporate all types of information into an experience that I never had."

Back