Prof. Wade Hazel Part of an International Research Team Published in Current Biology

March 29, 2011

March 29, 2011, Greencastle, Ind. — When it comes to wooing the ladies in a crowded room, an evolutionary biologist at DePauw University has found that tough guys trade their combat capability for mobility. Wade N. Hazel, Winona H. Welch Professor of Biology at DePauw, contributed to research which is published in Current Biology.

March 29, 2011, Greencastle, Ind. — When it comes to wooing the ladies in a crowded room, an evolutionary biologist at DePauw University has found that tough guys trade their combat capability for mobility. Wade N. Hazel, Winona H. Welch Professor of Biology at DePauw, contributed to research which is published in Current Biology.

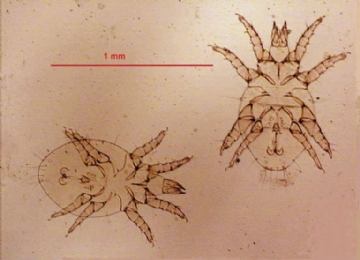

The study, conducted at the University of Western Australia when Dr. Hazel visited there on sabbatical, focuses on a mite, Rhizoglyphus echinopus, that has two different types of male: ‘fighters’, which turn one of their four pairs of legs into weapons that are used to kill their rivals; and ‘scramblers’, which possess a full complement of normal legs, and are incapable of harming each other.

The researchers maintained populations of the mites in two different types of habitats for ten generations and then looked at how the two alternative male types had evolved over time. Some populations lived in a ‘simple’ habitat, on a flat plain of plaster in Petri dishes, while others lived in a more three dimensionally ‘complex’ habitat in which the plaster was forested with upright drinking straws. (below right: two male mites fighting over a female; image by Piotr Lukasik)

Although the fighter males may have the advantage of their thick spiked legs when it comes to fighting off rivals, the researchers found that they suffer in a complex  environment because they are less mobile. Because the scrambler males are unencumbered by weaponized legs, they are more nimble and put this to their advantage in the complex habitats by more rapidly locating mates.

environment because they are less mobile. Because the scrambler males are unencumbered by weaponized legs, they are more nimble and put this to their advantage in the complex habitats by more rapidly locating mates.

The international research team, which included investigators from three continents, found that after living for ten generations in the complex habitats the mites evolved to produce fewer fighters, with only the very largest males becoming fighters.

It was Charles Darwin who in 1871 first proposed that evolution could account for the presence of weapons in male animals if the reproductive benefits of the weapons exceeded their cost. The results of this study, which manipulated the cost to benefit ratio of the male weapons, provide strong experimental support for Darwin’s idea. (image at left shows the two male forms; the one on the top right with the enlarged third pair of legs is the fighter morph; by Jacek Radwan)

“What’s neat about our results is that we were able to construct habitats that altered the cost to benefit ratio for weapon production and then let evolution take its course,” says Professor Hazel. “Evolutionary theory predicts that the decreased fitness of the fighters should lead to a decline in their frequency  over evolutionary time; and this is what we saw in a surprising short period of time.”

over evolutionary time; and this is what we saw in a surprising short period of time.”

He adds, “What happened was that the reduced mobility of fighter males in the three dimensionally complex habitats limited their access to females and reduced the benefits of having weapons.”

Joe Tomkins of the University of Western Australia, who led the study, notes, “Our results show how important the complexity of the environment can be to evolutionary outcomes, few studies have been able to manipulate this as we have done.”

Access the text by clicking here.