News & Media

Professor Michael Mackenzie

May 31, 2011

Associate

Professor of Art Michael “Mac” P. Mackenzie led his students through the doors

of a gallery in the Richard E. Peeler Art Center. As they began their

tour, he told the class to turn on their smartphones (maybe a first for a

college professor) and open up Facebook (ditto). There, Mackenzie had created a

virtual gallery of earlier works that had been “remixed” by the pieces on

display.

“Part of this exhibition was to show that contemporary art from the 1980s and 90s has passed into art history,” he says. “In order to make this point in the classroom, I would do what art historians have done for a hundred years: project two slides side-by-side. But I can’t do that in a gallery. I decided to make use of the technology that our students have in their pockets, and a network they are all connected to.”

Technology has changed the way art historians such as Mackenzie talk about art. Now, when he finds himself in a conversation about a particular work, there’s no reason to rely on recollection alone. Detailed images of nearly any work of art are only a few touchscreen presses away. For students hesitant to enter serious conversation about art, technology gives them a seat at the table.

"Students don’t always understand the power they have," Mackenzie says. "They carry around the history of art with them all the time."

Of course, even without wireless reception, Mackenzie has studied art history long enough to have the luxury of knowledge – of an artist who painted what, when and why. One artist, in particular, has held Mackenzie’s interest since his own time as a student.

Works by Otto Dix are immediately recognizable. Like many European artists at the beginning of the 20th century, his experience as a soldier in World War I – a war that introduced mechanized tanks and chemical warfare to the battlefield – deeply affected his art.

“It was much, much more violent than any war previously, and in some ways since,” Mackenzie says. "And in a sense, it accomplished nothing. So, it required explanation. A lot of people who fought were then engaged with trying to figure out what it meant to them individually, and then as German or French or British, and that’s what a lot of the art or literature is about: trying to manage that conversation.”

When Mackenzie was a graduate student, so much had been written about Dix that original observations were hard to come by. But recently, after reading a book by literary critical Mikhail Bakhtin, Mackenzie felt he had something new to add to the conversation of Dix’s post-war work.

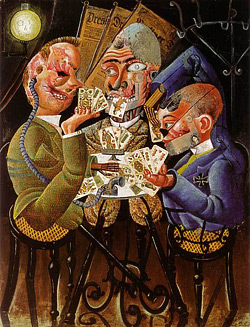

Dix depicted

the war with almost cartoonish horror. Bodies, disease and filth fill the trenches, and even the living are unrecognizably human. (left: Otto Dix's Die Skatspieler, 1920)

Dix depicted

the war with almost cartoonish horror. Bodies, disease and filth fill the trenches, and even the living are unrecognizably human. (left: Otto Dix's Die Skatspieler, 1920)

“The obvious explanation was that Dix felt that the war ruined his generation and he thought the best way to condemn the war was to represent it realistically,” Mackenzie says. “But that always seemed to leave something out. It didn’t seem to be the whole story.

“Bakhtin had a theory about grotesque realism. He believed that grotesque humor was a way for people to deal with death. This idea suddenly gave me a way to explain what Dix was doing. I asked myself, if he was writing about language, wouldn’t it be likely that soldiers in the trenches had some kind of language that would be grotesque, and would have all these metaphors than came from the body – a slang that would be funny and help them ward off this constant fear of death? I did a little research, and it turns out that they did. In fact, people have written glossaries of slang terms that soldiers used, and Dix was also interested in them. I went to an archive in Germany, and, in his diary, in the margins where you’d expect drawings, he also wrote lists of these slang terms. He was fascinated by them. I have this idea that the grotesque realism in his work is an attempt to find a visual equivalent for that slang. Other veterans of the war who looked at his art were going to get it. They were going to recognize this humor in a way that those who didn’t fight would not.”

Mackenzie is now working on a new book about Dix and the dark humor that art historians have always had a hard time coming to terms with.

In addition to his research, Mackenzie teaches courses about contemporary and Indian art – he travels to India this summer through ASIANetwork's Faculty Enhancement Program – as well as modern artists such as Dix. Modern art, he says, provides a topic that has aged enough to fit within the realm of art history, but new and challenging enough that it continues to spark debate in and out of his classroom.

“Even a hundred years after the fact, modern art still has the ability to make people ask, ‘Why is that art?’ and to follow up with the complaint, ‘Anybody could have done that,” Mackenzie explains. “Those really are valid questions and observations, and I don’t think that’s a misunderstanding of it. My job is to tell the story, to explain how art became this way.

“Modern art is a dialogue, but not one in which we come to the table with all the answers. It’s valuable for students to be confronted with that uncertainty, and I think that’s what makes it a great liberal arts discipline. It demands real intellectual engagement from its audience.”

Contact Us

Communications & Marketing

Bob Weaver

Senior Director of Communications

- bobweaver@depauw.edu

- (765) 658-4286

-

201 E. Seminary St.

Greencastle, IN 46135