Science Road Show

Maria T. Haag '13 presenting her research at NCUR in April

May 8, 2013

Entering the final week of her tap dance class, senior Maria T. Haag was having trouble remembering parts of her last performance of the semester, if not her life. Frankly, her mind had been elsewhere during the month leading up to it. Her body, too; she and members of Associate Professor of Biology Pascal J. Lafontant’s heart regeneration lab spent much of April barnstorming conferences from Wisconsin to Washington, D.C., to share their findings. If Haag’s tap fails to impress, at least her lab’s research can steal the show.

Swimming around in your dentist’s aquarium, zebrafish might not seem very impressive, but they – and at least one other member of the cyprinid family – have an ability that should make us mammals jealous: They can regenerate damaged heart tissue. For the past few years, Lafontant has overseen students in multiple lines of research using these fish, believing that if their mechanism for regeneration can be used to treat heart disease in humans, the leading cause of death in the United States might drop a few spots in the rankings.

Compared to the hundreds of billions of dollars spent each year treating heart disease, the lab’s operating budget isn’t even a small drop in the bucket. But with test subjects that can be found at a local pet shop and a group of hungry, go-getting undergraduate research assistants, his lab is proving how far ingenuity can go in biomedical research.

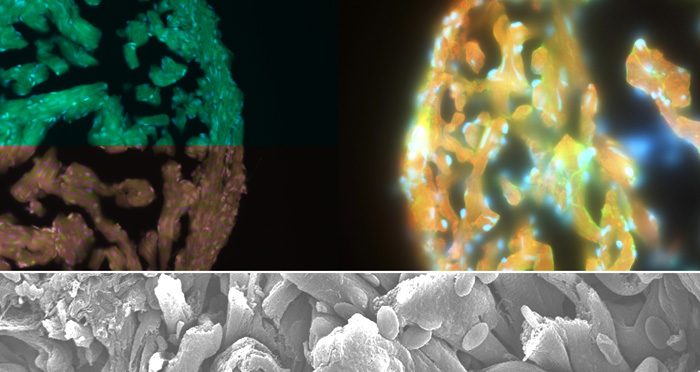

Top: Image of a fish heart ventricle captured by a flourescence microscope. Bottom: A ventricle as seen by an electron microscope. The lab relies on various methods of microscopy to determine whether regeneration is taking place.

In 2011 a student research team led by Tanmoy Das Lala ’12, now at Weill Cornell Medical College at Cornell University, showed that another cyprinid called the giant danio could also regenerate heart tissue. That spring, Das Lala was one of 12 students invited by the American Association of Anatomists (AAA) to present research at a poster competition during Experimental Biology (EB) 2011, one of the largest conferences of its kind. He won first place, and with it, early recognition for the lab’s work.

Haag, who joined the Lafontant lab as a junior, took over where Das Lala left off. His research showed that heart regeneration among the cyprinids wasn’t unique to zebrafish, but was it common across the entire family? Haag set out to find just how widespread the trait was using goldfish, a distant cousin of the giant danio and zebrafish. The initial results, she says, have been encouraging.

“It’s early, but all signs are pointing to the fact that regeneration in goldfish is occurring,” Haag, a member of DePauw’s Science Research Fellows, says.

Haag traveled in mid-April to present her research at the National Conference on Undergraduate Research (NCUR) at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse, and the following week to EB 2013 in Boston to compete in the same competition Das Lala won two years prior. And just as her predecessor had, she won, too. But this victory was just a little bittersweet. It’s one thing to go up against 11 students from colleges across North America; it’s another to have one of those students, senior Adedoyin E. Johnson, come from your own lab.

Johnson began investigating the effect of the anticancer drug doxorubicin on the giant danio as a sophomore. “It was a new project when I got involved, and I was one of the first people to start working on it,” Johnson, who is from Nigeria, says. “That really made it special to me.” Used in the treatment of many types of cancer, one of the doxorubicin’s potential side effects is a heart dysfunction called cardiomyopathy that can develop years or even decades after the drug was administered. Since joining the lab, Johnson has tested whether the same side effect occurs in the fish – and whether regeneration continues to take place – which would make the species a potential test bed for cardiomyopathy research.

“There’s a long way to go, but what we know for sure is we see the same effect in fish as we do in mammals when we inject the drug,” Johnson says. “Now we have to check how fish will handle side effects and whether regeneration occurs as it does in other forms of injury.”

Though Johnson (on right, with Lafontant at EB 2013) came up short in Boston, her April was somehow even more of a whirlwind tour than Haag’s. After both presented in Wisconsin and Boston, Johnson was one of 60 students invited to Washington, D.C., to share research with members of Congress at the Council on Undergraduate Research’s Posters on the Hill event. Earlier in the year, Haag and Johnson also presented at the Indiana Physiological Society’s annual conference, where Johnson won Best Abstract by an Undergraduate Student.

Though Johnson (on right, with Lafontant at EB 2013) came up short in Boston, her April was somehow even more of a whirlwind tour than Haag’s. After both presented in Wisconsin and Boston, Johnson was one of 60 students invited to Washington, D.C., to share research with members of Congress at the Council on Undergraduate Research’s Posters on the Hill event. Earlier in the year, Haag and Johnson also presented at the Indiana Physiological Society’s annual conference, where Johnson won Best Abstract by an Undergraduate Student.

Their travels continue later this year as Johnson enters Tulane University’s Ph.D. program in biomedical sciences and Haag departs to study large animal genetics at University of Missouri – her EB 2013 prize money, she says, is already earmarked for apartment furniture.

In the months leading up to graduation, the lab’s seniors have balanced their own work with preparing the newer members to take over for them. “You spend a lot of time on your research, so you get very invested in it, but you also know in the back of your mind that there is an expiration date for the time that you’re here,” Haag says. “I think that’s why you do start working with the younger students and trying to make sure they understand what’s going on and how to do it.”

The Lafontant Lab, Spring 2013: (l-r) Anderson J. Antoine '13, Kathryn M. Manalo '16, Trina M. Manalo '14, Maria Haag '13, Julia E. Roell '16, Adedoyin E. Johnson '13, Adam S. May '16, Khadijah Crosby '14, J'nai A. Macklin '14, and Professor Lafontant.

Research projects typically span longer than the four years most students spend in college, and the ones undertaken by the Lafontant lab are no exception. In Lafontant’s published study, of the six students named – Jamie A. Grivas ’10, Mary Ann Lesch ‘10,Tyler D. Frounfelter ’09, and Das Lala as co-authors, and Benjamin L. Golden ‘10 and Amanda R. Miller ’11 as contributors – only Das Lala remained on campus at the time of publication. By then, many others had used their time in the lab to vault into graduate programs and med schools around the country just as Haag and Johnson will do in the fall.

“Some students spend half of their time at DePauw working in the lab,” Lafontant says. “They end up with lab experiences equivalent to what they would be exposed to in the early phases of a graduate program.”

It’s a rare win-win-win scenario: research on the fish may uncover a fountain of youth for the human heart, the lab’s reputation (and perhaps its budget) grows year by year, and Lafontant’s students gain the kind of research experience that trains them to be leaders in biological and biomedical sciences.

“I teach the student about research in a real-world sort of way,” Lafontant says. “It prepares them to do well in grad school, not only in the techniques they learn in the lab but also more importantly in their development as independent scientific thinkers. Most people are not aware of the work undergraduate students can do, so we need to educate them. A few awards here and there definitely help.”

Back