News & Media

Portrait of a Marine

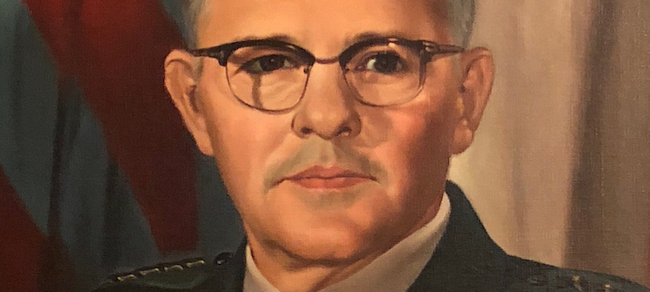

General David M. Shoup '26

November 11, 2017

Once described as “the bravest Marine who ever wore the uniform,” General David M. Shoup ’26 earned his reputation on and off the battlefield.

During the Battle of Tarawa in 1943, Shoup and his men were wading ashore when they met with fierce resistance from entrenched Japanese forces. Shoup suffered a shrapnel wound to his leg and a grazing bullet wound to his neck during the initial assault. Despite his injuries, he and his men overtook Tarawa’s beach defenses under a rain of artillery fire. The following day, as his wounds became infected, Shoup continued the assault inland until reinforcements arrived.

Shoup received the Congressional Medal of Honor for his bravery on Tarawa. The citation reads: “By his brilliant leadership, daring tactics and selfless devotion to duty, Col. Shoup was largely responsible for the final decisive defeat of the enemy.”

In 1959, President Dwight D. Eisenhower appointed Shoup Commandant of the Marine Corps. Later, Shoup was known as President John F. Kennedy’s “favorite general,” and when President Lyndon B. Johnson pinned the Distinguished Service Medal on General Shoup in 1964, he described him as “strong enough to prevent a war and wise enough to avoid one.”

Gen. David Shoup '26 joins President Kennedy during Veteran's Day 1962 at Arlington National Cemetary

Gen. David Shoup '26 joins President Kennedy during Veteran's Day 1962 at Arlington National Cemetary

General Shoup’s portrait, which he gifted to DePauw University in 1963, continues the story where Johnson left off — and begins a new one.

John A. Kellogg ‘62 (MA ‘69) remembers first seeing the portrait while a graduate student at DePauw in the late 1960s. But shortly after he took a job in the admissions office in 1970, the portrait was moved from its prominent location in the Student Union Building to the Air Force ROTC.

Kellogg understood the decision. “After all the upheaval started on college campuses, I think the University was worried people would deface it because it was in such a public place,” he says.

But the move also worried him. ROTC buildings were often the targets of vandalism during the Vietnam War, and DePauw’s AFROTC had recently survived an arson attempt of its own.

Kellogg had more reason to care about the painting than perhaps any other person on campus. He’d served on active duty in the Marine Corps from 1962-66. What’s more, General Shoup had signed his officer’s commission.

“That’s kind of a big deal for a Marine,” Kellogg says. “So, I had an emotional connection to the painting. I just didn’t want anything to happen to it.”

In 1973, when Kellogg started hearing chatter about the AFROTC leaving campus, he immediately thought of General Shoup’s portrait. Kellogg called the officer in charge, who told him that no decision had been made about where to move the painting. A few months later Kellogg called to ask again.

“He was kind of chuckling, so I could tell that the plans for the painting were ambiguous,” Kellogg recalls. “I just said, ‘Tell you what, I’m going to come get it.’”

[Click to view full portrait]

Kellogg walked across campus, removed the painting from the wall and carried it under his arm back to the Studebaker Administration Building to hang in his office.

“I figured if somebody was interested in where [Shoup] went they could come find him,” he says.

Kellogg left DePauw in 1974 and later joined the administration at Simpson College in Indianola, Iowa, where he retired as vice president of marketing and research in 2006. The portrait stayed behind at DePauw, kept in storage for the remainder of the war. It now hangs on the first floor of East College.

The fear of anti-war vandalism that kept Shoup’s portrait on the move adds an ironic layer to the story: both Shoup and Kellogg were opposed to American involvement in Vietnam.

After retiring from the Marine Corps in 1963, Shoup became an outspoken critic of nearly all military intervention abroad, particularly in Southeast Asia. During a speech he gave at Pierce College in 1966, Shoup didn’t hold back:

“I believe that if we had and would keep our dirty, bloody, dollar-soaked fingers out of the business of these nations so full of depressed, exploited people, they will arrive at a solution of their own. And if unfortunately their revolution must be of the violent type because the "haves" refuse to share with the "have-nots" by any peaceful method, at least what they get will be their own, and not the American style, which they don't want and above all don't want crammed down their throats by Americans.”

As for Kellogg, he’d left active duty on the verge of a promotion. “I was ready to make captain, but I got out,” he says. “I was against Vietnam. I would have gone if I’d have gotten the order, but I wasn’t about to extend voluntarily.”

Though Shoup and Kellogg never met, many things connect the two men: their Marine Corps service, an alma mater, a war both distant and close.

And an old portrait, filled with stories.

Contact Us

Communications & Marketing

Bob Weaver

Senior Director of Communications

- bobweaver@depauw.edu

- (765) 658-4286

-

201 E. Seminary St.

Greencastle, IN 46135