Perhaps the fates decided it was time for the Pogue family to experience some good fortune.

The family certainly had had its share of disaster. Henry Edgar Pogue in 1876 bought the Maysville, Kentucky, distillery where he worked and re-established it as Old Pogue Distillery, only to be killed on site in 1890, when a tail on his suit coat – distillers dressed formally back then – got inextricably caught in machinery.

His son, Henry Pogue II, took over the distillery and was meeting great commercial success, only to be killed in a similar accident in 1919.

His son, Henry Pogue III, having recently returned from U.S. Navy service in World War I, took over the distillery. But the 18th Amendment, which banned alcoholic beverages, had been ratified in January 1919 and, when Prohibition took effect a year later, Pogue was relegated to making limited quantities for medicinal purposes. He even bought a couple more distilleries to do the same, but he couldn’t stay afloat. The Pogue distillery ended operations in 1926.

Prohibition ended in 1933, and Pogue III – soured on operating his own distillery – became a consultant to upstart distilleries. In 1935, he sold the business to a Chicago company that renovated the distillery and produced bourbon for 18 years before shifting to fuel production during World War II.

So much for Old Pogue bourbon. Until a moment of serendipity changed everything.

“I graduated from law school in 1989 and my dad brought out a box that had corporate minutes in it and he said, ‘Now that you’re a lawyer, I thought you’d like to read the corporate minutes,’” said Peter Pogue, a 1983 graduate of DePauw University and Henry Pogue’s great-great grandson. Peter’s father, Jack, was Pogue III’s son.

They were Old Pogue documents. Modern members of the Pogue family were vaguely aware of the family business but, like Peter, whose law practice is in Indianapolis, had pursued careers far removed from the distilling business.

Peter’s brother Paul, a 1975 DePauw graduate, then was an oral and maxillofacial surgeon in Evansville. John, a 2007 DePauw graduate and, as the son of Jack’s brother Henry Pogue V, is their first cousin once removed, would become a geologist doing environmental cleanups for the city of Portland, Oregon.

"John pretty much walks on hallowed ground every day. He walks in the footsteps of six generations of his family who did the same thing and is able to bring that legacy back. For me, as a prideful part of it, that’s pretty cool."– Peter Pogue

“And I’m like, yeah, those are great, but what’s this here?” Peter recalled. “And he said, ‘Oh, yeah, well, those are the original recipes.’ And I said, well, now we’re talking. And we would get together on the Fourth of July in Evansville or in Kentucky at Christmas and we’d say, ‘Wouldn’t it be great? Wouldn’t it be great?’ And we’d always say no, we don’t know anything about it, and we’d put it on the shelf for another year.”

Still, the allure of the family legacy was strong, and the topic of “what if” resurfaced during numerous family gatherings. This, even though Henry III had extracted a promise from his children – including Jack, Peter and Paul’s father – that they would never go into the bourbon business that had so stung his family.

“We would always say, we agree, but he never made us promise that,” Peter said.

When the banter grew more serious, Jack arranged for his sons to meet in spring 1996 with his friend Sam Cecil, who had been a distiller at some of Kentucky’s most prominent distilleries.

“Our dad, who was a veterinarian by trade, thought that Sam was going to shut us down and say, ‘You guys don’t have a clue; you don’t know anything about the business. Just go away.’ And we had lunch with him and he looked over all the original recipes and he would look at my dad and finally he said, ‘You all are one of the original bourbon families in Kentucky. Everybody else is owned by a big conglomerate that’s international. You have to do this.’”

And they did. Intending only to have a hobby that allowed them to spend more time together, the Pogues embarked on reviving the family legacy and have turned it into a thriving, small-batch distillery producing products that have been praised widely by those who know premium bourbon.

They started in 1998 by identifying a Bardstown, Kentucky, distiller (its identity is a closely held secret) that would use their recipes – updated, with Cecil’s help, to modern standards – to distill Old Pogue products, which reached the market in 2004.

“It was just luck when we decided to start because bourbon didn’t really take off until, I don’t know, five, six years later,” Paul said, “and, by that time, we were at least regionally established, even though we were super small compared to the big players. Then about, I guess, ’09, ’10, craft just really came on the scene and it has spread like wildfire, in almost every state.”

Another stroke of luck occurred in 2009, when a three-acre property next to the site where the original distillery once stood came on the market. The property included a house that Henry II’s widow, Annabelle, sold in 1953 and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The family snatched it up.

This prompted more conversations: “Should we keep having things done for us in Bardstown or should we really think about maybe doing some things on a small scale over here?” Peter said. “And so we took that leap of faith.”

Nearly 60 years after bourbon was last produced in the immediate vicinity, the Pogue family began distilling on the family homestead, which is registered as the third distilled spirits plant in Kentucky. As best as they can tell, they are the only family to own a bourbon distillery before and after Prohibition.

Paul, then nearing retirement, built on his science background to become the weekend distiller. “With our first batch, we thought among ourselves, we may have Christmas presents for life,” he said. “We didn’t know if we could ever sell it. …

“We all got together at least Thanksgiving and Christmas every year, because the six of us were spread out … but this was a way maybe we could get back together more often. We went from twice a year to talking on the phone three or four nights a week.” (In addition to the DePauw contingent, Peter and Paul’s four siblings and John’s father, Henry V, are owners. Jack had come around and also was an owner before his death in 2015.)

Those conversations led to what John called “a precipice” – should they increase production or call it quits? Would he return to Kentucky – he grew up in nearby Fort Thomas – to become a full-time distiller?

“It just got to that point around 2011 where someone needed to come and take the helm, and I was happy to do it,” John said. “Ultimately, it came down to math – the statistical kind of approach where I was one of 300 registered geologists in the state of Oregon, versus being one of about 20 people who were responsible for 95% of the world’s bourbon. I am probably better off going to make bourbon.”

Persuading John to return, Paul said, “turned out to be the biggest stroke of luck for us. I still had a day job then and I wasn’t going to be making a lot, coming over one weekend a month. So we didn’t really have a plan going forward.”

They do now. With John on site, the distillery produces about 130 barrels a year, and the plan is to phase out all production at Bardstown over the next two years. Old Pogue Master’s Select, a bourbon, and Old Maysville Club, a rye, are the flagship brands, made in regular rotation and available at the distillery and in Kentucky, Illinois and New York. Other recipes – there are eight in all – are used to produce what the family calls “one offs” – products made for even more limited distribution, such as Port of Kentucky and Old Mason County, both bourbons, and Five Fathers, a rye malt whiskey.

“We try things to keep it interesting,” Paul said. “And we’re always looking for better. We do have just those main two products that we try to keep going all the time … and whether we ever have any that are widely distributed other than those two, I don’t know that we want to.”

The products’ names pay homage to the historical significance of Maysville, which was an important Ohio River port dating to the Revolutionary War.

“We try to do everything that’s integral to the history and heritage of this area because it is one of the most historical areas in the entire United States,” Peter said.

“John pretty much walks on hallowed ground every day. He walks in the footsteps of six generations of his family who did the same thing and is able to bring that legacy back. For me, as a prideful part of it, that’s pretty cool. …

“Our only rule is that John can’t wear tails to work.”

De Pogues discuss DePauw

Peter ’83 (left): “One of the things that I loved about DePauw was the fear factor: You had to be prepared when you went to class, because with only 10 or 12 people in your class, you knew that you were going to get called on, and you knew you had to be prepared. And that’s something that I needed at that stage of my life, as a teenager. Law school was simple for me because of the preparation that I got at DePauw.”

Paul ’75 (center): “Given DePauw’s reputation, it was kind of a no-brainer. I didn’t really start out knowing that I wanted to go more the science route, but that’s what worked for me in high school. It took me a year and a half to figure out that that’s what worked for me at DePauw. I just did the general courses and then did science through to the end. DePauw definitely helped me get into professional school, dental school.”

John ’07 (right): “The class size at DePauw, in particular, really won the day for me in my visits there. And then once I was actually boots-on-the-ground at DePauw, the rigors of my major and the geosciences department really prepared me for the professional world beyond what I saw in my colleagues. In hindsight, it was definitely the right choice. … It gave me the capacity to approach unique endeavors, like starting a distillery or dealing with complicated federal regulations in the environmental world.”

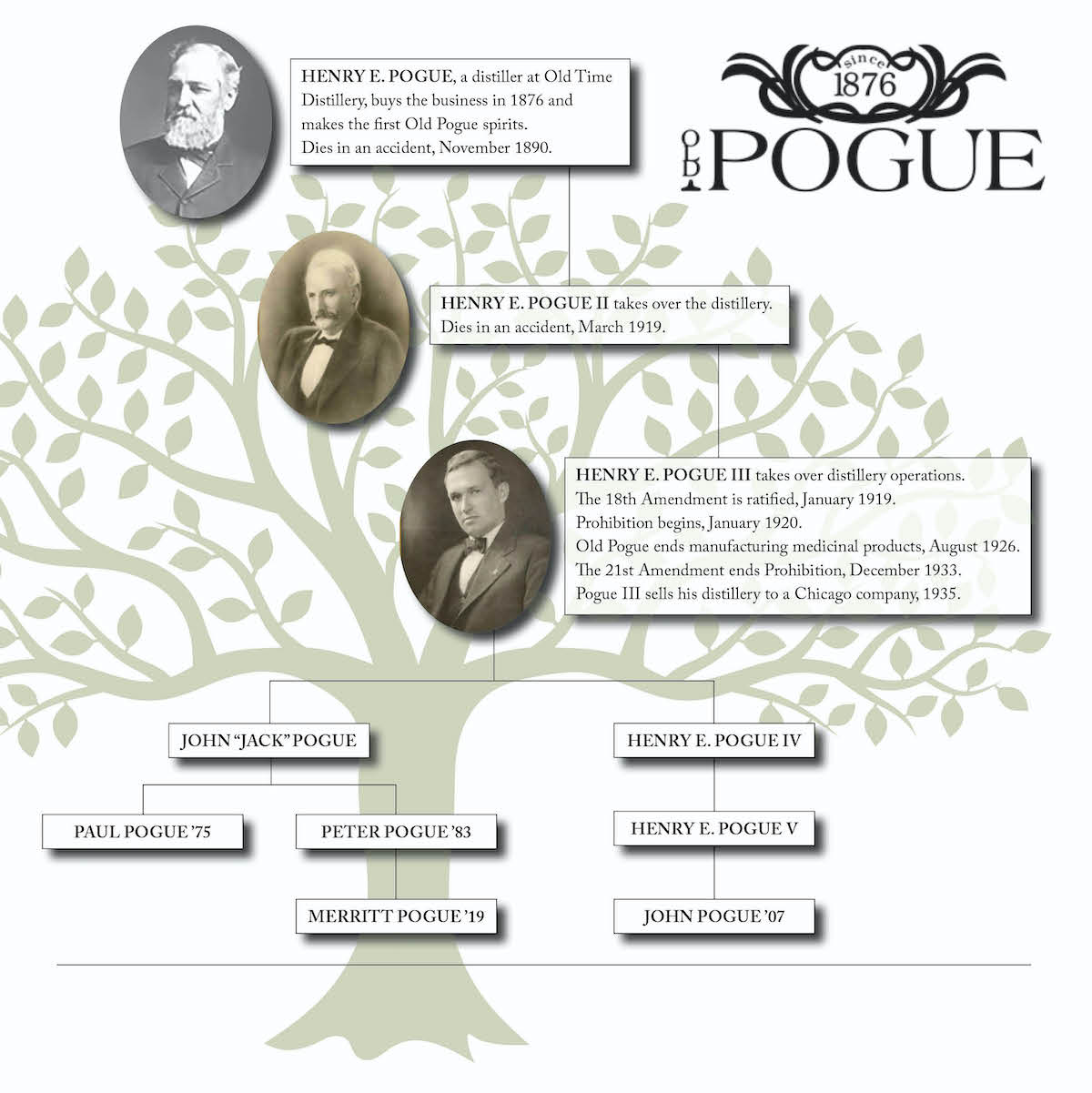

Pogue family tree

John’s brother is also a DePauw alum – Benjamin Pogue ’02. They have DePauw connections on their maternal side too:

grandmother Julia Christian Dillon ’31; uncle James Dillon ’62 and his wife Susannah Harger Dillon ’60; uncle Daniel Dillon ’64 and his wife Catherine Hash Dillon ’65; cousin William Dillon ’87 and his wife Sarah Clark Dillon ’87; cousin David Dillon ’91; and two first cousins once removed, Julia Dillon ’17 and John Dillon ‘19.

In addition to Peter (president), Paul (vice president), and John, the distillery is owned by

Jack’s other children, Jack Jr. (treasurer), Mary Milliner, Amy Pogue and Robert “Bo;” and by John’s father, Henry Pogue V (secretary).

DePauw Magazine

Spring 2020

Leaders the World Needs: Alum who attended college against odds guides youths to do same

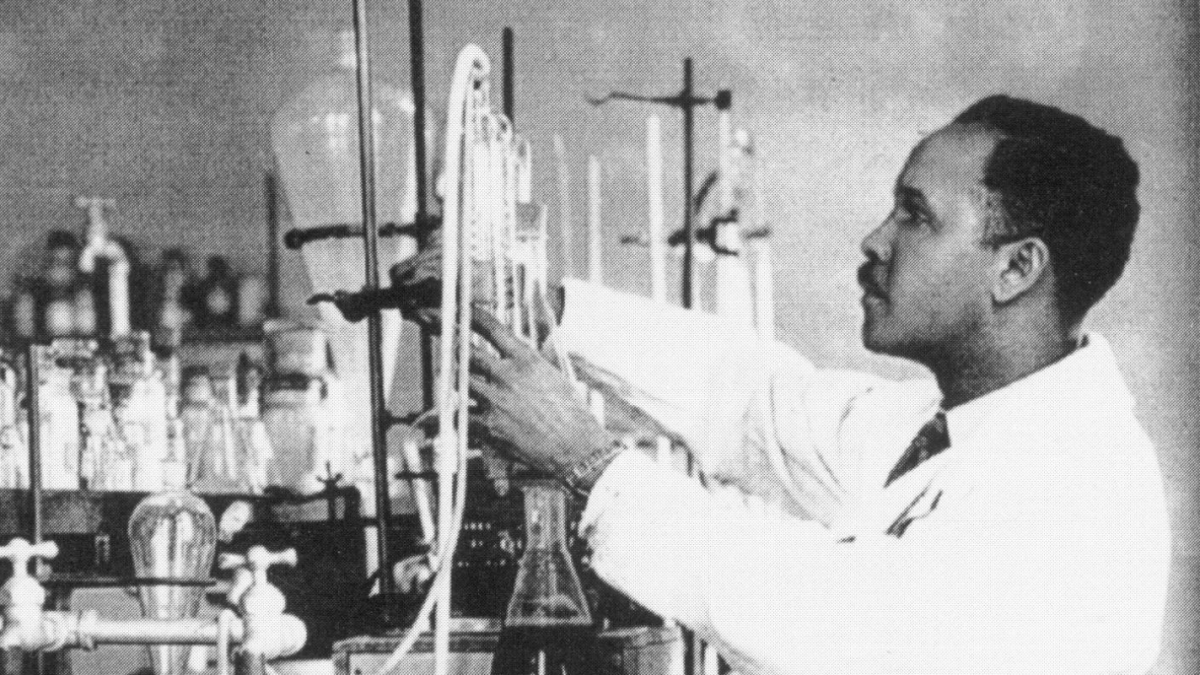

Leaders the World Needs: Alum who attended college against odds guides youths to do same OLD GOLD: Percy Julian, unappreciated in his time, inspires today

OLD GOLD: Percy Julian, unappreciated in his time, inspires today FIRST PERSON with Jonna McGinley Reilly '00

FIRST PERSON with Jonna McGinley Reilly '00  The Bo(u)lder Question By Rebecca Bordt

The Bo(u)lder Question By Rebecca Bordt The poet

The poet The iceman

The iceman The most American athlete ever

The most American athlete ever

The beekeeper

The beekeeper The juggler

The juggler The lucky guy

The lucky guy Aligned stars: Snowshoeing scientist studies the skies

Aligned stars: Snowshoeing scientist studies the skies Indelible images: Devastating photo, desperate need move alums to act

Indelible images: Devastating photo, desperate need move alums to act The nonconformists

The nonconformists A twist of fate: Unexpected discovery rekindles family legacy

A twist of fate: Unexpected discovery rekindles family legacy

DePauw Stories

A GATHERING PLACE FOR STORYTELLING ABOUT DEPAUW UNIVERSITY

Browse other stories

-

Athletics

-

Women's Tennis - DePauw Advances to NCAC Semifinals with 4-0 Win over Wooster

-

Men's Lacrosse - Tigers Fall to Wittenberg

-

Baseball - DePauw Tops Rose-Hulman in Home Finale

More Athletics

-

-

News

-

Little 5 makes big splash through philanthropy and service

-

Greencastle Celebrates National Main Street Day with Small Business Breakfast, New Program Launch, and Spring Pitch Competition

-

Hirotsugu "Chuck" Iikubo ’57 remembered as thoughtful leader, advocate for international goodwill

More News

-

-

People & Profiles

-

11 alums make list of influential Hoosiers

-

DePauw welcomes Dr. Manal Shalaby as Fulbright Scholar-in-Residence

-

DePauw Names New Vice President for Communications and Strategy and Chief of Staff

More People & Profiles

-

-

Have a story idea?

Whether we are writing about the intellectual challenge of our classrooms, a campus life that builds leadership, incredible faculty achievements or the seemingly endless stories of alumni success, we think DePauw has some fun stories to tell.

-

Communications & Marketing

101 E. Seminary St.

Greencastle, IN, 46135-0037

communicate@depauw.eduNews and Media

-

News media: For help with a story, contact:

Bob Weaver, Senior Director of Communications.

bobweaver@depauw.edu.