First Person

is a regular feature of DePauw Magazine, which is published three times a year.

In fall of 2016, I found out that an incurable cancer had taken lodging inside me. My diagnosis arrived as an uncanny coincidence. I was writing an essay called “Psychedelic Last Rites,” which compared the Catholic sacrament of extreme unction with modern experiments in which scientists give psychedelic drugs to terminal cancer patients. In both the traditional sacrament and the new experiments, the goal is to help dying people find peace as they manage their last days. Then suddenly, mid-draft, I joined the ranks of dying penitents and clinical subjects. The synchronicity of the moment struck with such force that it felt surreal; I had arrived at the cosmic threshold that just a few hours before had seemed a benign abstraction.

In my own quest for equanimity and cosmic composure, I have been relying on other resources. Three of the last courses I taught at DePauw provided invaluable help. One was a longtime favorite on the British Romantics. John Keats’s “To Autumn” held particular significance now: it was likely the last poem Keats finished, a quiet landscape charged with the emotions of a young man dying. He observes a field at sunset,

While barred clouds bloom the soft-dying day

And touch the stubble-plain with rosy hue.

I love how Keats marries life and death here. The day is simultaneously dying and blooming; sunlit clouds make roses out of stumps. Teaching that poem for the final time, I recognized more clearly than ever a deep truth that fortifies my spirits. Life and death are not really opposites, or even two separate things at all: “lifedeath” is what we have.

The very last course I taught at DePauw was “The Seven Deadly Sins.” The topic may not sound so comforting, on the face of it: maybe not the best time to study medieval panic about eternal damnation! But I found another helpful perspective in our study of pride. Pride is a bit of an oddball. Regarded by many theologians as the most dangerous of the deadly sins, it is also the only one routinely used in expressions of praise (“You must be so proud!”). Pride presents such a dire threat to souls, according to Thomas Aquinas, because it conceals itself so well: people do not recognize its presence. Might our fear of death be understood as a particularly well-camouflaged manifestation of pride?

I have one more course-related encouragement to mention. The students from my 2015 first-year seminar found out about my diagnosis. They crafted a wooden box full of letters they had all written to me. To these I added other letters as they came in from former students after the news spread. I was taken aback by how elaborate my box was – decorations, fancy hinges, even an ornate carrying handle. I thought, it’s like something from an Egyptian tomb, packed with treasures to use in the journey through the underworld. And that’s exactly what it is. I carry these treasures with me every day as I manage my own version of the journey.

Glausser taught English at DePauw from 1980 until he retired at the end of the 2017-18 academic year. He is receiving immunotherapy treatments for metastatic melanoma and, as a result, “I’ve lasted way beyond my expiration date.”

DePauw Magazine

Summer 2020

The Bo(u)lder Question

The Bo(u)lder Question  Retired archivist reflects on 36 years as DePauw’s memory keeper

Retired archivist reflects on 36 years as DePauw’s memory keeper First Person by Connie Campbell Berry '67

First Person by Connie Campbell Berry '67 First Person by Wayne Glausser

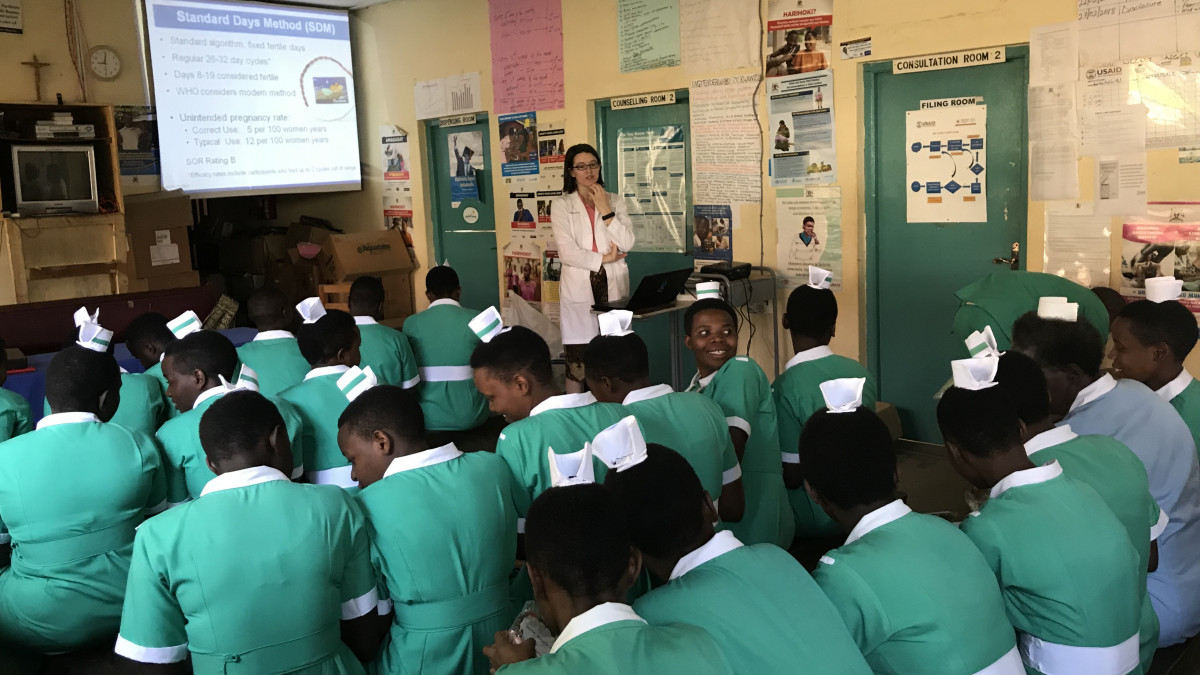

First Person by Wayne Glausser Battling an epidemic, treating individuals: Physician alum has done it all

Battling an epidemic, treating individuals: Physician alum has done it all  Welcome, Class of 2024!

Welcome, Class of 2024! She has loved them since she was 6: vet cares for, competes with and rescues horses

She has loved them since she was 6: vet cares for, competes with and rescues horses Liberal arts taught wildlife vet to consider different approaches to patients’ problems

Liberal arts taught wildlife vet to consider different approaches to patients’ problems Scientist and humanitarian: Prof embodies disparate interests, then acts on and teaches them

Scientist and humanitarian: Prof embodies disparate interests, then acts on and teaches them Researcher follows the science toward treatments

Researcher follows the science toward treatments The ‘dura mater’ handles medical training and motherhood with aplomb

The ‘dura mater’ handles medical training and motherhood with aplomb  Evolving interests drive ’12 grad to trade test tubes for a stethoscope

Evolving interests drive ’12 grad to trade test tubes for a stethoscope Alum hopes to meet global needs by establishing med school

Alum hopes to meet global needs by establishing med school The healers

The healers Personal experiences prepared ’76 alum for work, service

Personal experiences prepared ’76 alum for work, service DePauw in the time of COVID-19

DePauw in the time of COVID-19 DePauw’s new president: A ‘visionary,’ empathetic and focused optimist ... who sings

DePauw’s new president: A ‘visionary,’ empathetic and focused optimist ... who sings

DePauw Stories

A GATHERING PLACE FOR STORYTELLING ABOUT DEPAUW UNIVERSITY

Browse other stories

-

Athletics

-

Women's Golf - Williams Selected NCAC Women's Golf Athlete of the Week

-

Women's Lacrosse - Tigers Score 24 Against Illinois Wesleyan

-

Men's Golf - Tigers Finish 12th at Music City Shootout; "B" Team Places Fifth

More Athletics

-

-

News

-

Resident Assistants Nurture Community and Connection

-

Francesca Seaman Speaks the Language of Mentorship

-

DePauw Announces $10 Million Matching Challenge for Student Scholarships

More News

-

-

People & Profiles

-

Empie, Party of Five: One Family’s Unique DePauw Bond

-

Entrepreneurs Eric Fruth ’02 and Matt DeLeon ’02 Are Running More Than a Business

-

Rick Provine Leaves Legacy of Leadership and Creativity

More People & Profiles

-

-

Have a story idea?

Whether we are writing about the intellectual challenge of our classrooms, a campus life that builds leadership, incredible faculty achievements or the seemingly endless stories of alumni success, we think DePauw has some fun stories to tell.

-

Communications & Marketing

101 E. Seminary St.

Greencastle, IN, 46135-0037

communicate@depauw.eduNews and Media

-

News media: For help with a story, contact:

Bob Weaver, Senior Director of Communications.

bobweaver@depauw.edu.