Jonna McGinley Reilly '00 practices law in Chicago and represents clients across the country in intellectual property and commercial litigation matters. In late 2019, she volunteered at the southern border for Las Americas Immigrant Advocacy Center. She worked with the Detained Deportation Defense program, interviewing detainees at El Paso Processing Center and Otero County Processing Center, New Mexico.

My rental car barrels south en route to the Presidio Chapel of San Elizario. A story plays on the local radio about covers of Tom Waits’s songs, and a halting female voice sings, “Why wasn’t God watching? / Why wasn’t God listening? / Why wasn’t God there…?”

The Presidio, one of three churches that compose the El Paso Mission Trail, sits squarely in the United States, but hasn’t always. A gradual shift in the path of the Rio Grande quite literally unmoored it. Almost 200 years ago, the Presidio sat on the south side of the Rio Grande and, had I visited then, I would have been in Mexico.

The Presidio, one of three churches that compose the El Paso Mission Trail, sits squarely in the United States, but hasn’t always. A gradual shift in the path of the Rio Grande quite literally unmoored it. Almost 200 years ago, the Presidio sat on the south side of the Rio Grande and, had I visited then, I would have been in Mexico.

Just before visiting the Presidio, I spent a week using my background as an attorney to interview non-citizens captured by Immigration and Customs Enforcement crossing this once-fluid border or found to be living in the United States without proper documentation. Now held in various detention centers, they face deportation. I assessed their claims for asylum or alternative immigration relief, hoping to collect sufficient facts to enable the legal aid center I’d traveled from Chicago to volunteer for to take their case.

***

I spent my first few days in Texas at the El Paso Processing Center, which can house more than 1500 people, both men and women.

No windows exist in the white-and-grey-painted cement block room I interview detainees in. Most of them speak only Spanish. I use a translator. We sit on metal benches bolted to the ground. The doors lock from the outside; neither I nor the detainee may leave the room without knocking on the door and waiting for a guard to release us. To earn the prison-style jumpsuit every detainee wears, most legally presented themselves at the U.S. border and asked for asylum.

I meet María from Guatemala, whose eyes well with tears when I outline the five grounds for asylum. She whispers, “I don’t think I qualify,” in Spanish. María left the only town she’d ever known after her uncle, a government official, raped her disabled sister. María took what she could carry, including her younger sister, and fled. When they arrived at the U.S. border, border patrol separated the siblings, owing to the disabled sister’s minor status. María fears returning to Guatemala, but more urgently she fears no one is looking out for her sister.

I whisper, “lo siento.” “I’m sorry.” I repeat myself countless times over the course of a week. I learn the word “siento” in Spanish means “feel” so the literal meaning of “lo siento” is “I feel it.”

There’s a sewer line that runs underground from Juarez, Mexico, into El Paso. I meet Lilian, who crawled through it. Once a lawyer, Lilian left Honduras 15 years ago after attempts were made on her life for refusing to defend a drug trafficker. When Lilian’s fingerprints were analyzed as part of the application process to become a legal permanent resident, a decade-old order of removal was discovered. Unaware of potential relief available to her, Lilian was deported, leaving behind her two minor children. Upon her return to Honduras, the same people who previously threatened her life learned of her return. She hid. Then she fought her way back, crawled through a tunnel of waste, and tried to return to her family.

Angela, a mother, discovered the promise of democracy when she went abroad to secure an expensive wheelchair for her terminally ill daughter. She returned to her home country of Cuba, watched the government confiscate the wheelchair at the airport and began advocating with an underground opposition group working to secure medical care for children. Officials tracked her down, beat her up. They forced her to perform a sex act, threatening to arrest her mother. She left Cuba with the hope of a better life for her daughter.

Ernesto, a young man also from Cuba, endured years of abuse – starting when he was in high school – at the receiving end of police officers’ fists when he refused to join the local Communist party. As a national election approached, the assaults escalated. Ernesto fled to Nicaragua to Honduras to Guatemala to Mexico. Unfortunately, he did not request asylum in any of them. At the time, he did not know he needed to in order to secure protection in the United States.

At the end of each day, I knock on the metal door, walk through three more metal doors, then step outside. The warm wind slaps me in the face and the southwestern sun instantly burns my skin, reminding me the rest of the world carries on as if this processing center does not exist.

***

After three days in El Paso, I travel to Otero County Processing Center, New Mexico. I speed north, past the audacious beauty of the Franklin Mountains. By the time I arrive at Otero, the enormity of the humanitarian crisis our nation faces threatens to defeat me.

A thousand male (or transgender) migrant detainees live at Otero, hidden in plain sight in the middle of the desert. The cold, stark rooms at the El Paso center seem luxurious in comparison. Here, a wall of glass separates the detainees. There are no chairs. One metal stool is bolted to the ground. The small room where I work is hot, but not everyone gets a private meeting room.

In the hallway outside our door, a young family meets with a detainee, separated by the glass window. Mom places her baby girl, a pacifier in her mouth, one-inch pigtails sprouting from her head, against the window and she slaps her pudgy hands against the glass as dad, on the other side, traces her fingers and tears stream down his face. When they leave, I hear the little boy’s tiny cowboy boots click down the hallway.

Across the hall, we meet a person who now goes by “she” and who was gang-raped by homophobic police officers in Honduras. Whose testicles were cut from her body. Who asked for refuge at our border. I had no concept of how much depravity existed in this world. With increasing frequency, the stories in the news ring true.

Marco brought his three-year-old daughter to the U.S., where she was separated from him at the Texas border. Though Marco provided contact information for family legally present in the U.S., his daughter was sent to Pennsylvania. Weeks later, miraculously, family was able to locate her. Months later, they were finally reunited. Days later, a social worker advised that she had been sexually abused. No one knows who harmed her. No one will likely ever know. She is, after all, only three.

Her father weeps. I whisper “lo siento.” Marco looks me in the eyes. I feel it.

After four days of hearing stories of horrific abuse by foreign nationals, and terrible conditions in communist regimes, and bitter stories of lives left behind, and families torn apart in the quest for a better life, I feel unmoored. Why wasn’t God watching when Marco’s daughter was torn from her father? Why wasn’t God listening when someone hurt her? Why weren’t we?

If the course of a river can change, why can’t we?

(Pseudonyms were used to protect the identity and confidentiality of detainees.)

First Person

is a regular feature of DePauw Magazine, which is published three times a year.

DePauw Magazine

Spring 2020

Leaders the World Needs: Alum who attended college against odds guides youths to do same

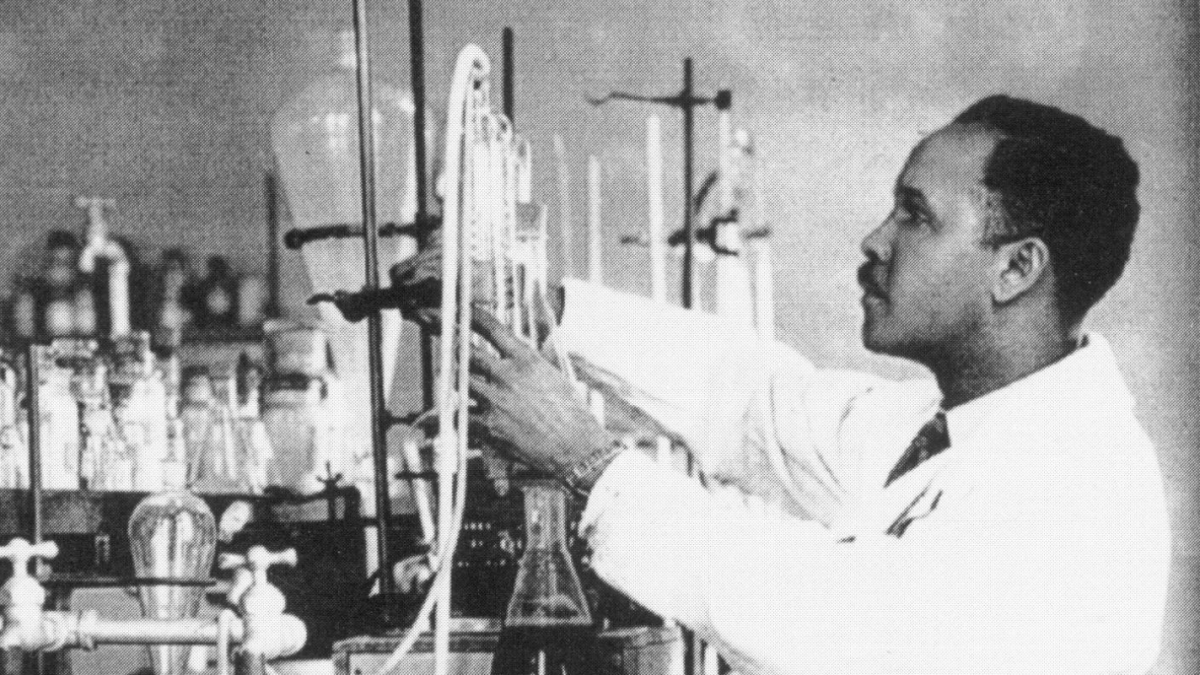

Leaders the World Needs: Alum who attended college against odds guides youths to do same OLD GOLD: Percy Julian, unappreciated in his time, inspires today

OLD GOLD: Percy Julian, unappreciated in his time, inspires today FIRST PERSON with Jonna McGinley Reilly '00

FIRST PERSON with Jonna McGinley Reilly '00  The Bo(u)lder Question By Rebecca Bordt

The Bo(u)lder Question By Rebecca Bordt The poet

The poet The iceman

The iceman The most American athlete ever

The most American athlete ever

The beekeeper

The beekeeper The juggler

The juggler The lucky guy

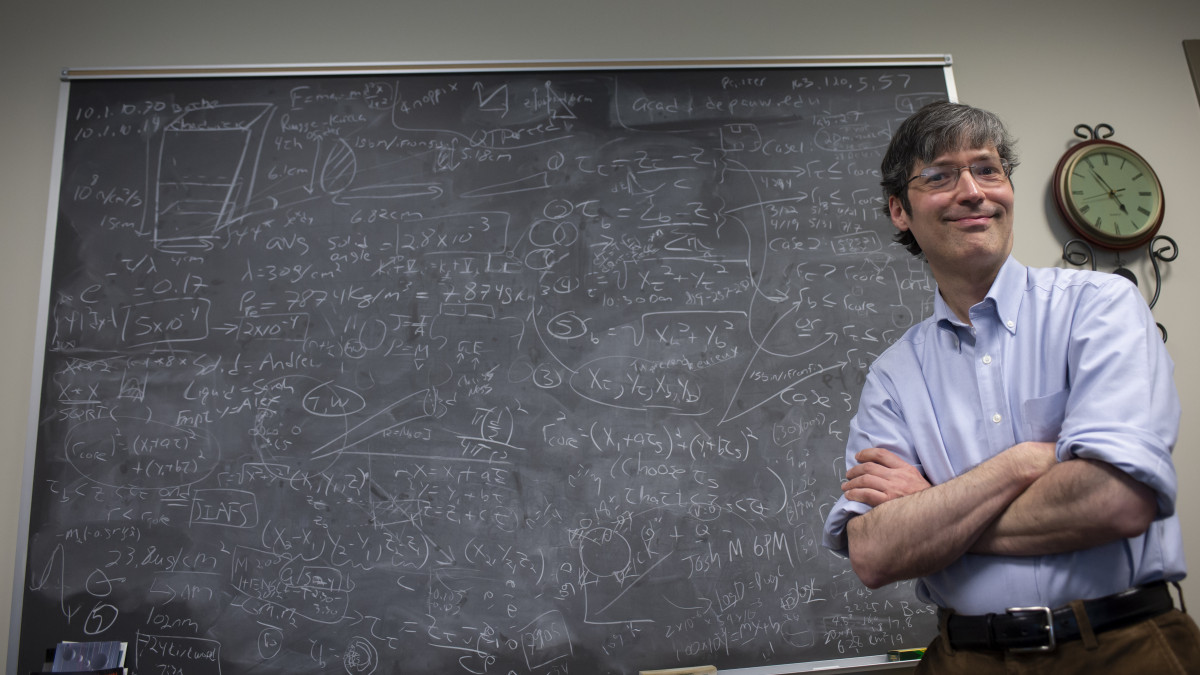

The lucky guy Aligned stars: Snowshoeing scientist studies the skies

Aligned stars: Snowshoeing scientist studies the skies Indelible images: Devastating photo, desperate need move alums to act

Indelible images: Devastating photo, desperate need move alums to act The nonconformists

The nonconformists A twist of fate: Unexpected discovery rekindles family legacy

A twist of fate: Unexpected discovery rekindles family legacy

DePauw Stories

A GATHERING PLACE FOR STORYTELLING ABOUT DEPAUW UNIVERSITY

Browse other stories

-

Athletics

-

Football - Robby Ballentine Selected Associated Press First Team All-America

-

Men's Basketball - Hot-Shooting Tigers Win Fourth Straight

-

Women's Swimming & Diving - Laba Chosen NCAC Women's Swimming and Dviing Athlete of the Week

More Athletics

-

-

News

-

Student and Professor Share Unexpected Writing Journey

-

Four in a Row! DePauw Wins 131st Monon Bell Classic

-

Jim Rechtin '93 Featured in Fortune Magazine

More News

-

-

People & Profiles

-

Entrepreneurs Eric Fruth ’02 and Matt DeLeon ’02 Are Running More Than a Business

-

Rick Provine Leaves Legacy of Leadership and Creativity

-

History Graduate Cecilia Slane Featured in AHA's Perspectives on History

More People & Profiles

-

-

Have a story idea?

Whether we are writing about the intellectual challenge of our classrooms, a campus life that builds leadership, incredible faculty achievements or the seemingly endless stories of alumni success, we think DePauw has some fun stories to tell.

-

Communications & Marketing

101 E. Seminary St.

Greencastle, IN, 46135-0037

communicate@depauw.eduNews and Media

-

News media: For help with a story, contact:

Bob Weaver, Senior Director of Communications.

bobweaver@depauw.edu.