Amber McNamara ’97 looked at the gopher tortoise lying on the treatment table and considered her options.

The creature had been hit by a car, and was dragging her back legs. The veterinarian had treated wildlife with medications typically used for domestic animals, “but at some point, you run out of treatment options,” she said, “and this tortoise was very amenable to receiving acupuncture and physical therapy.”

The creature had been hit by a car, and was dragging her back legs. The veterinarian had treated wildlife with medications typically used for domestic animals, “but at some point, you run out of treatment options,” she said, “and this tortoise was very amenable to receiving acupuncture and physical therapy.”

And thus McNamara, trained in traditional veterinary medicine at Purdue University’s College of Veterinary Medicine, tapped her less traditional training – she is certified in veterinary acupuncture – to treat her patient.

“Eventually she was able to walk again,” McNamara said. “And eventually, released. So it is really amazing to see. And even though it’s a slow progression, it was progression and movement in the right direction.”

McNamara is an associate professor of biology at Lees McRae College in North Carolina and a veterinarian at its May Wildlife Rehabilitation Center, where more than 1,500 injured and orphaned wildlife patients were treated last year.

A biology major and math minor at DePauw, McNamara had always loved animals but credits a winter-term experience shadowing a vet for helping her envision how her love of science and her compassion for animals jibed.

A biology major and math minor at DePauw, McNamara had always loved animals but credits a winter-term experience shadowing a vet for helping her envision how her love of science and her compassion for animals jibed.

Her track took a turn toward the unusual when she was in veterinary school and worked a six-week externship at a wildlife clinic in Florida.

“I really loved the idea that every day was different,” she said, “and it really felt good at the end of the day to feel like you were doing something positive, not only for that individual animal but for the habitats in which they live and, to some extent, the environment and the ecology of the whole.”

After graduating from Purdue, McNamara interned at the Clinic for the Rehabilitation of Wildlife in Sanibel, Florida, then worked there for eight years.

After graduating from Purdue, McNamara interned at the Clinic for the Rehabilitation of Wildlife in Sanibel, Florida, then worked there for eight years.

“Wildlife medicine requires you to think quite a bit outside the box,” she said. “Since our patients are anywhere from two grams to 20 kilograms” – that’s seven-tenths of an ounce to 44 pounds – “solutions can be hard to come by.”

McNamara has had her share of bites and scratches, though nothing serious. “I try to teach the students that, even though we are trying to help the animals, to them, we are predators. We teach the students to handle the patients in a way that is both safe for the handler and minimizes the stress of the patient.”

Her liberal arts education taught to consider more than one way to approach a problem, she said. Her wildlife patients, including that gopher tortoise, often benefit from a different approach to healing.

She tries to impart the same sort of thinking to her students, and hopes they recognize that they can do good, “even if it’s just one small action,” she said. “It doesn’t always mean that we have a positive outcome. Sometimes the outcome is not what we hoped for, but if we can show compassion to an animal – even if that compassion means ending their suffering – they can do something good.”

She tries to impart the same sort of thinking to her students, and hopes they recognize that they can do good, “even if it’s just one small action,” she said. “It doesn’t always mean that we have a positive outcome. Sometimes the outcome is not what we hoped for, but if we can show compassion to an animal – even if that compassion means ending their suffering – they can do something good.”

DePauw Magazine

Summer 2020

The Bo(u)lder Question

The Bo(u)lder Question  Retired archivist reflects on 36 years as DePauw’s memory keeper

Retired archivist reflects on 36 years as DePauw’s memory keeper First Person by Connie Campbell Berry '67

First Person by Connie Campbell Berry '67 First Person by Wayne Glausser

First Person by Wayne Glausser Battling an epidemic, treating individuals: Physician alum has done it all

Battling an epidemic, treating individuals: Physician alum has done it all  Welcome, Class of 2024!

Welcome, Class of 2024! She has loved them since she was 6: vet cares for, competes with and rescues horses

She has loved them since she was 6: vet cares for, competes with and rescues horses Liberal arts taught wildlife vet to consider different approaches to patients’ problems

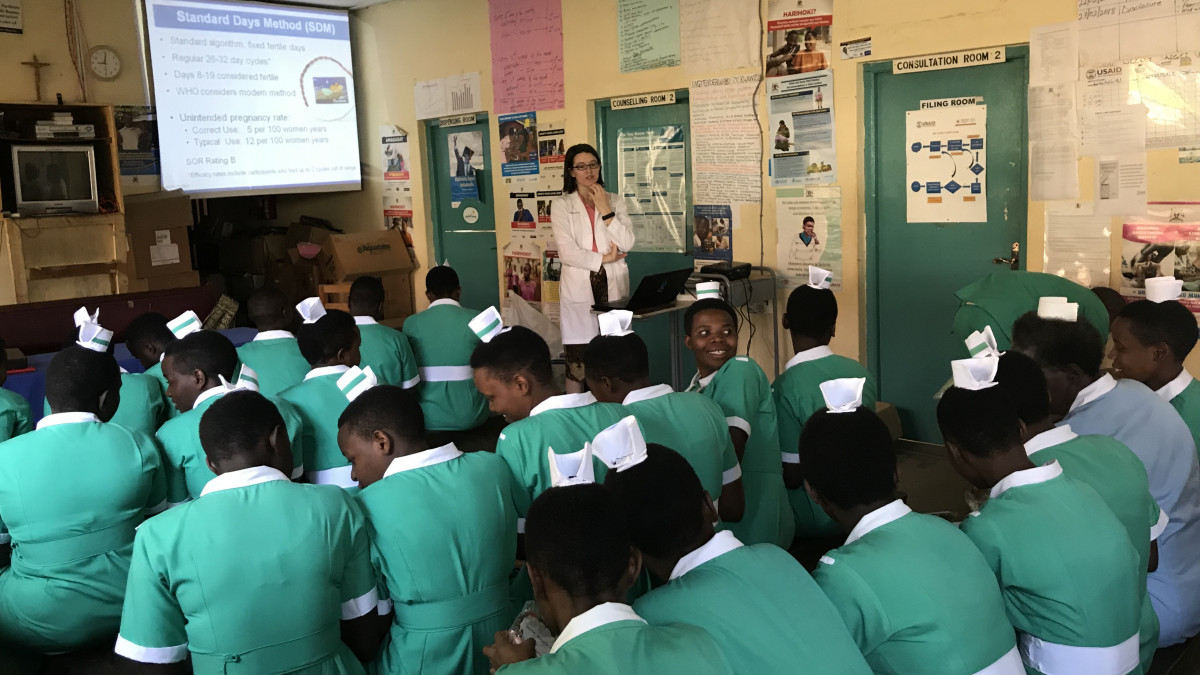

Liberal arts taught wildlife vet to consider different approaches to patients’ problems Scientist and humanitarian: Prof embodies disparate interests, then acts on and teaches them

Scientist and humanitarian: Prof embodies disparate interests, then acts on and teaches them Researcher follows the science toward treatments

Researcher follows the science toward treatments The ‘dura mater’ handles medical training and motherhood with aplomb

The ‘dura mater’ handles medical training and motherhood with aplomb  Evolving interests drive ’12 grad to trade test tubes for a stethoscope

Evolving interests drive ’12 grad to trade test tubes for a stethoscope Alum hopes to meet global needs by establishing med school

Alum hopes to meet global needs by establishing med school The healers

The healers Personal experiences prepared ’76 alum for work, service

Personal experiences prepared ’76 alum for work, service DePauw in the time of COVID-19

DePauw in the time of COVID-19 DePauw’s new president: A ‘visionary,’ empathetic and focused optimist ... who sings

DePauw’s new president: A ‘visionary,’ empathetic and focused optimist ... who sings

DePauw Stories

A GATHERING PLACE FOR STORYTELLING ABOUT DEPAUW UNIVERSITY

Browse other stories

-

Athletics

-

Baseball - Tigers Drop Twinbill to Little Giants

-

Men's Track & Field - Jansen Earns NCAC Field Athlete of the Week Honors

-

Women's Track & Field - Moore Earns NCAC Field Athlete of the Week Honors

More Athletics

-

-

News

-

Outstanding seniors honored with Walker Cup and Murad Medal

-

First-Year Trio Rolls to Pitch Competition Victory

-

Little 5 makes big splash through philanthropy and service

More News

-

-

People & Profiles

-

11 alums make list of influential Hoosiers

-

DePauw welcomes Dr. Manal Shalaby as Fulbright Scholar-in-Residence

-

DePauw Names New Vice President for Communications and Strategy and Chief of Staff

More People & Profiles

-

-

Have a story idea?

Whether we are writing about the intellectual challenge of our classrooms, a campus life that builds leadership, incredible faculty achievements or the seemingly endless stories of alumni success, we think DePauw has some fun stories to tell.

-

Communications & Marketing

101 E. Seminary St.

Greencastle, IN, 46135-0037

communicate@depauw.eduNews and Media

-

News media: For help with a story, contact:

Bob Weaver, Senior Director of Communications.

bobweaver@depauw.edu.